My name is Zog – get ready with me. I rise with the sun, nature’s alarm clock. Run my bone comb through my luscious beard and throw on my favorite fur vest. I grunt to my colleagues and start the morning with a breakfast of berries and roots (whole foods not Whole Foods if you catch my drift). Once I’m fueled for the day, I do a little DIY home renovation, fixing up my front door to make sure it’s rock solid and can keep out any unwanted guests. Finally, I’m ready to do some ol’ fashioned hunting and gathering to feed the crew.

I grab my trusty club and head down the path. I check the nearby patch of fig trees for fruit. I gather some nuts and seeds and then…

CRUNCH

I hear heavy footsteps getting closer and closer.

Heart rate increases.

Palms start to sweat.

Cross arms to protect my vital organs.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

Yes, a saber-toothed tiger is much scarier than a call from your boss, but it’s all relative, right? The new predator is the Outlook chime sound signaling a new email in your inbox. Despite this obvious difference in daily stressors, our physiological responses to stress have remained strikingly similar to our prehistoric compadres.

When confronted with perceived threats or stressful situations, our body’s “fight or flight” response kicks in. This innate physiological reaction, inherited from our caveman ancestors, prepares us for action in the face of danger. Hormones like adrenaline and cortisol flood our system, enhancing our senses, sharpening our focus, and mobilizing energy to react swiftly. This reaction served our ancestors well when escaping predators or battling rivals for limited resources, however, it’s not an ideal response for an 8PM email from your boss.

Fast forward to the modern workplace, where stressors may not be physical predators but emotional challenges and critical feedback (although Dave in accounting does let out some growls when expense reports are late). Surprisingly, our brains don’t always distinguish between a life-threatening situation and a performance review or feedback session. The fear of judgment, the anticipation of negative evaluations, and the pressure to meet expectations can trigger the same “fight or flight” response in our brains.

Overcoming the Feedback Dread

As much as our evolutionary past influences our responses to feedback, we have the power to shape our reactions consciously. By recognizing the physiological and psychological factors at play, we can start to change our mindset and embrace feedback as a catalyst for growth and improvement.

With this hypothesis in mind, to the public library we go! (Yes, JSTOR memberships aren’t cheap and my local library has stellar Wi-Fi).

DISCLAIMER: Building up a positive association with feedback is much like going to the gym. It can be hard work, progress takes time, and you might puke if you overdo it.

Finding #1: Solicit Feedback

As we discussed above, unsolicited feedback can cause the classic fight or flight response to trigger in our brains. But what if we took the surprise out of the equation? What if we knew the conversation was coming and we could control the variables?

A new study by NYU psychologist and NLI senior scientist Tessa West (“Asked For VS. Unasked For Feedback”) found that asking for feedback reduced the physiological stressors their study subjects faced – noted by heart rate spikes 50% lower than when they received unsolicited feedback. The content of the conversation isn’t necessarily the scary part, it’s the unpredictable nature of it.

Suddenly, we take a nerve wracking scenario and flip it on its head. When we ask for feedback, it gives us more control of the conversation, allowing feedback to be more specific and more impactful.

Finding #2: Invest in Relationships

Not all feedback can be solicited. Eventually, someone will find it necessary to share their perspective with us and we may not see it coming. With this in mind, what variables put us in a more receptive position to accept their point of view? What can help us to not fight, not flee, but instead to lean in?

Turns out, the person delivering the feedback makes all the difference. Research shows that developing trusting relationships with friends, colleagues, and bosses can significantly ease the anxiety around receiving constructive feedback (De Jong et al.; Dirks and Ferrin).

In a trusting relationship, feedback is perceived as coming from a place of genuine care and concern for the individual’s growth and development. The recipient is more likely to believe that the feedback is intended to help them improve, not criticize or undermine them.

What does this mean? We’re far more likely to be open to feedback from a work colleague or manager that we have a strong relationship with.

Manager Spotlight: Check out this article from the Harvard Business Publishing for tips on developing trust on your team.

Finding #3: Negativity Bias

We can’t always control the variables of a difficult conversation. Sometimes, we’ll receive feedback we didn’t ask for, from someone we don’t trust. The predator lurking in the shadows will make us want to run home to our cave and not come out again. So how do we cope?

When I was 12 years old my middle school class took a field trip to Williamsburg, VA. Here is a quick run-down of the highlights.

- Sat next to my best friend on the bus

- Stopped at McDonalds for lunch

- Assigned the cool chaperone that let us play Pokemon on our Gameboys

- Earned extra credit when I answered a question about the Continental Congress

Needless to say, it was pretty awesome. As we were leaving, it was time to buy souvenirs and from the moment we arrived I had been eyeing the super sweet colonial hat in the window of the gift shop. I reached into my jacket pocket to pull out my crisp $20 bill and…empty. I do the four pocket pat down, shake my jacket upside down. Gone. I still remember being absolutely crushed. I searched the bus. Interrogated my classmates. My day was ruined.

That, my friends, is Negativity Bias. In the paper “Bad Is Stronger Than Good”, the authors present compelling evidence to support the notion that negative experiences have a more profound impact on individuals than positive ones of similar intensity. Some studies have found that it takes five positive thoughts to offset one negative experience. Aka 12 year old Austin’s $20 loss ruined an otherwise perfect field trip.

How does this apply to feedback? In a similar way, people tend to weigh the disappointment of one negative criticism equal to five positive experiences. With the knowledge of the Negativity Bias in our back pockets, we can reframe negative feedback by consciously tapping into our bank of positive experiences we tend to minimize. Embracing a growth mindset is much easier when your self-esteem balloon is well inflated.

The Stress Cycle

Let’s revisit our caveman friend Zog. Approached by the predator in the woods, he had two options. Fight or Flight. Rumble with the big bad threat or sprint back to the comfy confines of his cave. Fight or Flight. Both physical endeavors.

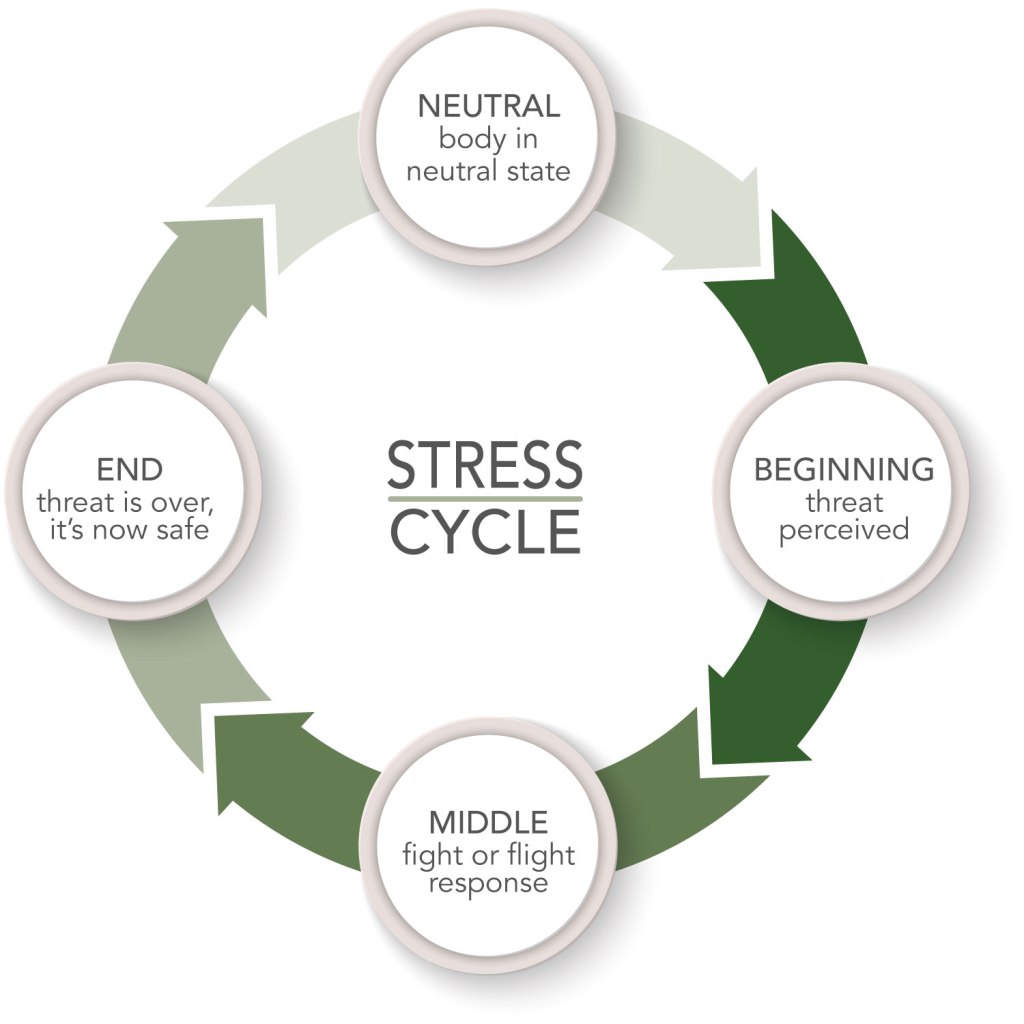

Remember earlier when I talked about the physiological response our body goes through during stress? That’s the start of the Stress Cycle, popularized by authors and psychologists Amelia Nagoski and Emily Nagoski in their book titled “Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle”. The stress cycle refers to the body’s natural response to stress and how it reacts when faced with challenging or threatening situations.

By fleeing danger, Zog makes it home safely after a frightening encounter. After his physical exertion he might feast or rest – but either way the stress cycle has a clear resolution.

But what about us? The difficult conversation with a colleague, slamming on the brakes in traffic, or a last minute childcare emergency all cause a similar physiological response. But instead of completing the stress cycle by actually fighting or fleeing, we worry at our desk or stay up at night thinking. Our bodies signaled danger but we never gave it the cue to relax.

Completing the stress cycle involves actively discharging the physiological responses associated with stress through various strategies like physical activity, emotional expression, mindfulness, and self-care.

So, the next time you face challenging feedback, don’t forget to run, dance, hug, or laugh your way through the stress cycle to let your body off the hook.

Leave a comment